As Xmas approaches, I present a really interesting guest blog from a member of Aletheia Coptic Apologetics Group. So few people today realise the incredible debt we owe to Christianity. Going on the words below, society today would be unimaginable had not that very special Baby been born two thousand years ago. Enjoy…

As often happens when one walks the streets of the Sydney CBD, I was once approached by a homeless woman who asked me for some money. In the conversation that followed, she commented on how irritated she was at the way city-goers would routinely snub her off and ignore her completely; “I mean,” she said, “I’m as human as everyone else.” I agreed with her of course. Who would deny as obvious a fact as that? Even those people who snubbed her and provoked the comment no doubt understood that although this woman was homeless, and lay considerably lower on whatever scale of social respectability we use to categorise ourselves nowadays, she was still as human as the richest person in Sydney. Her status as a member of the human race meant that she had a sort of inalienable value; she deserved exactly the same sort of basic respect and dignity as the richest and most successful members of our society, purely because she was a human being.

This might sound like a fact so obvious that it doesn’t really need to be said. All of us know perfectly well that a person’s social station does not reflect their value; we all understand that wealth and poverty, health and sickness don’t necessarily reflect any particular virtue or flaw in a person’s character, and that even if they did, we would be no less obliged to help any of our fellow human beings in need. How could we think otherwise? Isn’t that what it means to be human? In “Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies”, the Orthodox theologian and philosopher David Bentley Hart argues that if it weren’t for Christianity and its revolutionary re-imagining of what it means to be a human being, none of us might think that way at all. In the book’s introduction he says

“At a particular moment in history, I believe, something happened to Western humanity that changed it at the deepest levels of consciousness and at the highest levels of culture.”[1]

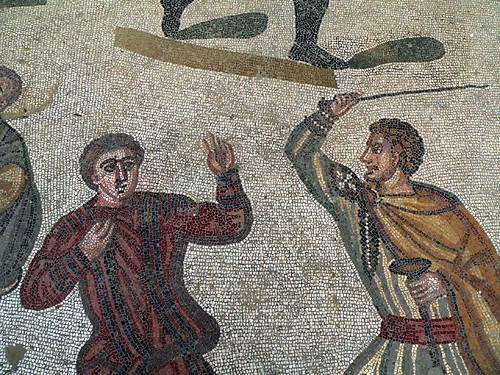

Living as we do, at the end of 2000 years of Christian history, in a culture that has been irrevocably shaped by the Christian view of the world, it is hard for us to appreciate just how revolutionary Christianity was when it first stepped onto the stage of history. We Copts know especially well that the Roman emperors were brutal and bloody in their repression of Christianity (half the icons that line our churches are the victims of Roman persecutions), but we do not, perhaps, appreciate why as well as we should. If Hart is to be believed, Christianity’s fundamental claims that God became man and died the death of a criminal, and that the sick, the poor and the sinful are as precious to God as any other of His children, were among the most subversive, rebellious and offensive ideas that the ancient world had ever encountered.

Modern readers might be surprised to find that one of the greatest problems the ancient pagans had with the early church was the ‘sort’ of persons they invited to their churches. Celsus, a pagan of the 2nd century AD, wrote:

“No wise man believes the Gospel, being driven away by the multitudes who adhere to it.”[2]

He harshly criticises the Christians for teaching wisdom to women, children and slaves, claiming that they only teach such people because they are unable to convince people of more ‘intelligent’ pedigree.[3] In saying this, he was merely echoing the soundest principles of classical wisdom; centuries earlier Plato[4] and Aristotle[5] had insisted that men, by nature, were superior to women, children and slaves. Such was the natural order, the way the gods had fashioned the world, and to treat slaves and women like men by teaching them and exhorting them to wisdom, was pointless stupidity.

He expresses a similar distaste for the way that Christians called ‘sinners’ to faith in Christ. Unlike most almost every respectable religion that came before it, the Christianity not only accepted but sought out prostitutes, drunkards and other ‘sinners’ in order to convert them to life in Christ. The outrage that this practice provoked in the minds of the ancients is readily apparent in the Gospels themselves; Christ’s contemporaries were repeatedly disgusted at the company He would keep (tax collectors, prostitutes, lepers etc.), and Christ would simply explain in response that He had come to save those who had need of saving.[6] While to us, Christ’s reason for behaving this way (“those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick …”[7]) makes perfect sense, to many of the ancients it was impious madness. Celsus complains that: “… no one by chastisement, much less by merciful treatment, could effect a complete change in those who are sinners both by nature and custom, for to change nature is an exceedingly difficult thing.”[8] For Celsus, sinners were sinners as much as women were women and slaves were slaves. It was ludicrous to think that one could change ‘what they were’ by any amount of correction or punishment. They simply were lesser, fouler members of the human race and no-one could or should attempt to change that. To attempt, as the Christians did by Christ’s example, to win sinners over by loving and serving them (or, to use a more modern term, by treating them as human beings) was the height of idiocy and bad taste.

To understand Celsus’ objections properly, it’s important to understand that pagan societies were heavily hierarchical[9] – they were very clearly ordered. Every person had their place on the grand ladder of social/religious importance; the emperor’s family, the wealthy landowners and the priests sat at the top of the ladder, while slaves, poor men, sinners and women tended towards the bottom (with occasional exceptions). It borders on being an undeniable fact that the people at the higher ends of the ladder were viewed as more ‘important’ and more ‘worthwhile’ than those at the bottom.

This is partly because, by and large, the pagans saw little difference between the spheres of ‘religion’ and ‘politics’. That is to say, your place on the social ladder reflected not only your political importance or your level of ‘authority’, but also reflected your virtue, your ‘worth’ in the eyes of the gods. As one author put it, “for the Romans, it was not true that all people are created equal.”[10] The gods had not created ‘humanity’ as we understand it today, a set of individuals who differ in ability, circumstances and social station but all share equal worth; the Roman gods had created rulers and subjects, masters and slaves, men and women, some of whom were made to rule and some of whom were made to serve.

Roman society was ordered in a way that reflected the superiorities and inferiorities that the gods had built into nature itself, and that notion of hierarchy pervaded every level of the Roman state, including the family. And it was the gods, captained by the great Creator God Himself, who preserved the hierarchy that held human society together; as Hart says, “the gods love order above all else.”[11]

Keeping all this in mind, think for a moment about Christianity’s fundamental historical claim: that God Himself became a lowly Jewish carpenter, spent most of His time preaching to and serving tax collectors, lepers and prostitutes, and was ultimately executed as a criminal. The extent to which this idea was a rejection of the pagan worldview is impossible to understate. In Hart’s rather forceful words:

“[To the pagans] the gospel was an outrage … this was far worse than mere irreverence; it was pure and misanthropic perversity; it was anarchy.”[12]

Christians claimed that the Creator God Himself, who should have been working to sustain and encourage the created order, had humbled Himself to its lowest level by taking the ‘form of a bondservant’[13] and dying the death of a criminal. And in so doing, He shattered, or even inverted the pagan hierarchy and brought into being a new order; an order in which “there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female” and where “all are one in Christ Jesus.”[14]

In other words, it is in Christianity that we first see the ideas of ‘humanity’ and the ‘infinite worth’ of every single human being regardless of virtue or social station, coming into being. Arguably, if it had not been for Christianity’s stunningly subversive teachings about the value of sinners and lower class peoples, such people might never have come to be considered fully ‘human’ at all. In Hart’s words, “it would not be implausible to argue that our very ability to speak of ‘persons’ as we do is a consequence of the revolution in moral sensibility that Christianity brought about.”[15]

Christianity is called a lot of things nowadays (dreary, outdated, dogmatic, evil …), but one character rarely applied to it is rebellious; which is rather ironic given that the early Christians (and their persecutors for that matter) inevitably understood themselves as rebels. Unfortunately, as modern Christians we rarely appreciate this sense of rebellion, even though it survives powerfully in our prayers and rites. It is nowhere more obvious than in the rite of baptism where the convert (or their parents if they are a child) turns to the West and declares:

I renounce you, Satan, with all your impure works, all your evil soldiers, all your wickedness, all your powers, all your despicable worship, all your deceiving and misleading trickery, all your armies, all your principalities and all the rest of your hypocrisy.

I renounce you! I renounce you! I renounce you!

The significance of these words to an ancient convert was absolutely life changing. In saying them, he was rejecting the pagan gods (who the Christians now began to call demons), and the human empire which they sustained – which is probably why early Christians refused to worship the image of the Roman emperor even on pain of torture and death.[16] By becoming Christians, they were confessing their allegiance to a new emperor (Christ) and a new order. And this new order rejected all the ‘hierarchy’ of the old, corrupt order; baptism washed away all pagan labels. Instead of a society based on rank and authority, the church was a community where all members bore the rank of the King Himself, for all Christians were said, by baptism, to have ‘put on Christ.’[17] In Christ’s church, even authority figures ought to humble themselves instead of ‘lording it over each other like the Gentiles’.[18] The Church also offered those whom the pagans despised as ‘sinners’ liberty from the rigid restraints pagan society had placed on them. In response to Celsus’ claim that it was near impossible to change the nature of a sinner, the Egyptian church father Origen replied that:

“for the word of God to change a nature in which evil has been naturalised is not only not impossible, but is even a work of no very great difficulty, if a man only believe that he must entrust himself to the God of all things.”[19]

And that was a definite difference between the pagan and early Christian views of humanity. Where the pagans (with some exceptions) saw only men, women, slaves and sinners who were what they were and could never be otherwise, the Christians saw a potential Christ in everyone. For Christians, the worldly wisdom[20] that ascribed different levels of worth different ‘sorts’ of people was an abomination. A Christian could not judge anyone’s worth based on their position in the social hierarchy, precisely because Christ had told them that even ‘the least of these’ warranted the respect due to the creator God Himself.

That is why Hart argues so passionately that if it weren’t for Christianity and it’s revolutionary ideas about the human race, the homeless woman I met on the street might never have thought to make the assertion that she was ‘as human as everyone else.’ For a pagan like Celsus, the idea that a homeless woman and the emperor himself shared some sort of equally respectable ‘nature’ may well have been not only ridiculous but an insult to the dignity of the emperor. Perhaps, if it had not been for the ‘Christian revolution’, many of our most cherished ‘modern’ ideals would not even have been possible.

Obviously, there’s a lot more that could be said about all this. There are questions like why, if Christianity was so revolutionarily egalitarian, Christians continued to keep slaves for so long (to which the short answer is ‘old habits die hard’), and many more. As a disclaimer, you’ll notice I’ve made a special effort to say ‘Hart argues’ or ‘according to Hart’ in much of the above rather than simply stating his arguments as facts, and this is because historical arguments this wide-ranging are hard to assess properly without a good level of historical knowledge, which I certainly don’t possess. Hart is a stunningly knowledgeable author however, and certainly, his arguments carry far more weight than the generally poorly informed historical arguments of the New Atheists. For those want to learn more, this is a beautiful, short and sweet summary of the argument:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FytwCHCniCk&feature=BFa&list=LL69h4BfHEoj4QkUWhBgHo1Q&lf=plpp_video

And of course, I highly recommend “Atheist Delusions” itself. It can be slow going at times, but Part 3 in particular presents one of the freshest and most inspiring visions of the Christian faith I have ever come across.

[1] DB Hart, Atheist Delusions pg. xiv

[2] Origen, ‘Against Celsus’, Book III, Chapter 73, (http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/04163.htm)

[3] Ibid., Book III, Chapters 54-58 (same URL as above)

[4] Plato, The Republic, Book IV, Part v (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1497/1497-h/1497-h.htm#2H_4_0007) (The relevant passage can be found by pressing Ctrl+F and searching for ‘servants’ – the few paragraphs above that give useful background to understanding Plato’s argument here)

[5] Aristotle, The Politics, Book VII, Part iii (http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/a/aristotle/a8po/book1.html)

[6] (Luke 5:30-32), (Luke 7:36-50)

[7] (Mark 2:17)

[8] Quoted in Origen’s Against Celsus, Book III, Chapter 65 (http://web.archive.org/web/20060427150628/http://duke.usask.ca/~niallm/252/Celstop.htm)

[9] Barbara McManus, Social Class and Public Display (http://www.vroma.org/~bmcmanus/socialclass.html)

[10] N.S. Gill, Roman Society, About.com – (http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/socialculture/tp/Roman-Society.htm)

[11] DB Hart, Atheist Delusions, pg. 173

[12] Ibid, pg. 115

[13] Phil 2:7 (Paul’s statement that Christ ‘did not consider it robbery to be equal with God’ makes a lot of sense when viewed in light of the pagan hierarchy; arguably, it was precisely this ‘robbery’, this pretension of a low ranking criminal carpenter to be the God that sat at the top of the created order that so infuriated Celsus and his contemporaries.)

[14] (Gal 3:28)

[15] DB Hart, Atheist Delusions, pg. 167

[16] (http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/pliny.html)

[17] (Gal 3:27)

[18] (Matt 20:25-26)

[19] Origen, ‘Against Celsus’, Book III, Chapter 69, (http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/04163.htm)

[20] (1 Cor 1:18-31) and (1 Cor 3:18)

Nice one Samuel! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Fascinating. Really liked it. The original Christians were rebels, and Christianity to them was nothing less than a peaceful and deep revolution in the soul and culture; and, slowly, in world order. Many underestimate the effect of this quiet and peaceful revolution but the word has never seen quite a thing like it. I am glad that you have pointed to that.

I have not read “Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies” by David Bentley Hart, but I will certainly order it now.

Dioscorus Boles

http://copticliterature.wordpress.com/

I believe christianity has made a historical move in the past and it really changed the world and all its content.